A behind-the-scenes glimpse at nursing

Nursing is kind of a mystery for most who are not in the healthcare industry.

What do we do all day?

Do we really save lives?

How do we cope with trauma and other things that we see?

Is it really as life-changing as everyone says it is?

I am going to attempt to answer these questions and more, and give you a little insight on my life in a twelve-hour night shift in the hospital.

First, though, I work in an ICU. This stands for Intensive Care Unit. My patients are all critically ill. I do not work in a specialized unit, so I can have any sort of illness from trauma, to neuro-trauma, to cardiac, to respiratory, and more. Most patients have breathing tubes because they cannot breathe for themselves, and a lot of them are on continuous medications to help with their blood pressure, or any number of other things. These drips need to be closely monitored to make sure that they are doing their job adequately. This is why we only have 1-2 patients.

I’ll start by giving you an overview of my shift.

I work from 7 pm to 7:30 am.

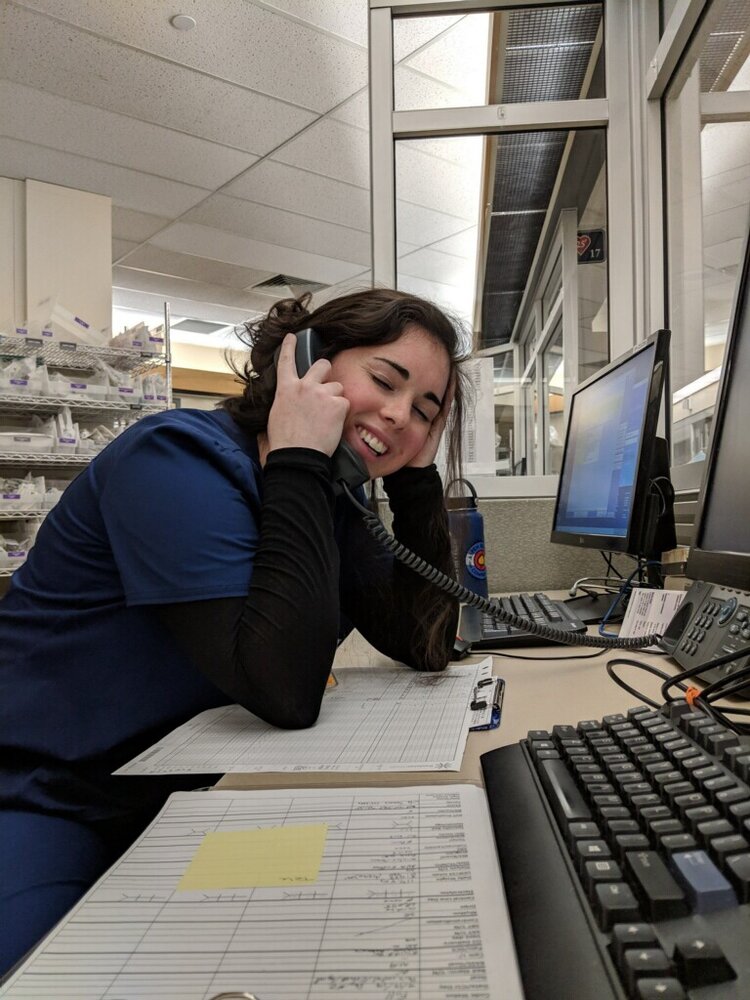

I start by getting a report about my patients (usually 2 patients, sometimes one if they are really sick) from the day-shift nurse. This takes anywhere from 15-20 minutes. We go over the story of why they are in the ICU, health history, an assessment of every body system, and any social aspects that might be helpful to know. This is also the time to share what occurred during day shift and the plan of care. We also make it a point to meet the patients together and introduce ourselves to make the transitions easier for the patients.

I try to spend some time (about 30 minutes) after report to look over my patients’ charts. I look at laboratory values, which include electrolytes, blood values, etc, any imaging reports such as CTs or X-rays, physician updates and reports, and nursing notes about the patients. I end this time by looking at medications that are due throughout the night. The first round of medications are usually due at 9pm.

I then gather the medications that are due, and I head into the patient’s room. I perform a full assessment on my patient at this time. This is my own assessment of each body system (neurological, respiratory, cardiac, abdominal, skin, etc). If the patient is able to speak, I’ll ask them questions as I go, but usually they are unable, due to a breathing tube, a neurological deficit, or something else. I also give my patient their medications. This isn’t a mindless task either; I have to ensure that all of my vital signs are within the parameters, and actually think through that my patient needs each medication.

I do this for both of my patients.

After I do this, I take the time to go through the room to clean it and get ready for the night. I like tidy rooms; clutter is unnecessary.

I also gather equipment I might need through the night for, say, wound dressing changes, baths, or any other orders that the physician wants done during the night.

Until around 3am, I am doing tasks in my patients’ rooms and monitoring them every hour for any changes.

At around 3-4am, I start my morning tasks. I draw blood on my patients for laboratory tests. When results of these come back, I have to look at all of the numbers and replace anything if the value is low. These could be electrolytes (potassium, magnesium, phosphorus), which have a large impact on the heart and blood pressure, or blood products if a patient is bleeding too much.

At around 5am, a radiology technician comes around with a portable x-ray machine and takes chest x-rays of my patients. This is to see how our patients’ lungs look, as well as breathing tube or central line placement verification.

By 6am, I have to have all of my charting completed. If I have cardiac patients, they both need to be up in chairs by 6:30am before the cardiac surgeon and his team do their rounds at 7am.

The mornings are always busy, but it’s helpful because that’s usually when I am the most tired.

This would be the perfect shift, but of course, it hardly ever goes like that. Patients need things, vital signs change unexpectedly, and we are always helping each other out in rooms that are more busy, or wherever a patient might be crashing (crashing: blood pressure decreasing, unable to breathe effectively, basically trying to die quickly).

So, do we really save lives?

Yes, actually!

Most of the patients in the ICU would not be living if we were not monitoring them, and giving medications, and titrating drips like we do.

If a patient’s heart stops beating during a night shift (we call this a code), nurses are the first to respond. We have been trained to give life-saving medications, do CPR, and shock those patients to get them back.

My most recent code I helped with was a few weeks ago. We ended up calling the physician to get orders while he drove to the hospital to help us, but the initial reaction is all nurses.

It’s pretty cool!

How do we cope when we see things like that?

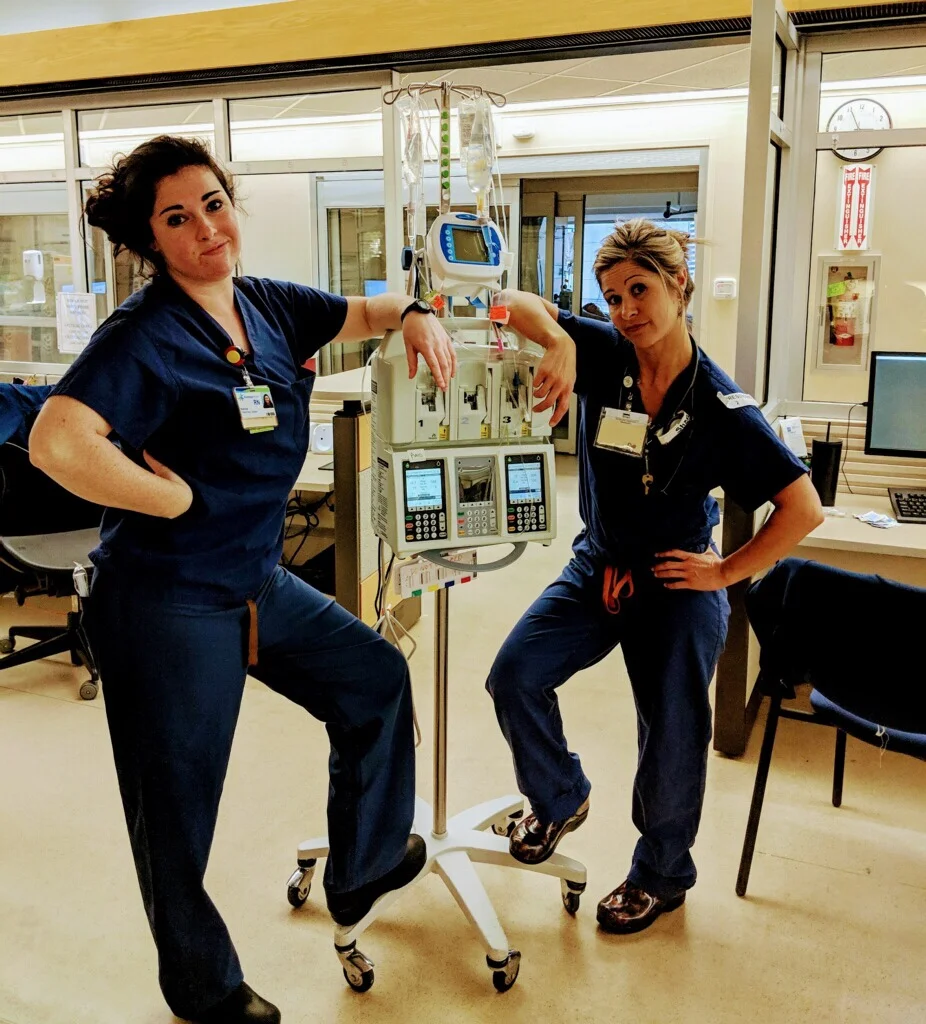

Humor.

I’d say our ability to laugh at kind of messed up things helps us cope.

We also try to debrief after big events.

This is when the physician in charge and the nurses involved get together and discuss the event; what went well, what we could have done better, ways to do self-care after the shift so that we don’t get burnt out.

We don’t always do a great job though, and burnout is a very real thing, especially in the ICU.

We see a lot of trauma, a lot of sad/tragic cases.

We fight so hard to help our patients live, and still we might not be successful.

We see families come together; see them torn apart.

See peoples’ lives change in an instant.

And even with writing this post, it does not do it justice to what I see, feel, and think everyday as an ICU nurse. It is life-changing.

It gives me perspective.

It makes empathy difficult. I see the very worst, making someone else’s “very worst” not as impactful if it isn’t as bad as other things that I have seen.

This has been a new realization for me.

Nurses want nothing more than to empathize with people.

But how can you empathize with a patient who overdosed on heroin, when your other patient took a fall and is now paralyzed from the neck down?

You have to, that’s how.

You have to realize that each person lives in their own world, and what might be horrible in one person’s world, might be a drop in the bucket for someone else’s world.

And it’s not my job to decide whose world is more heart breaking or sad.

It’s my job to empathize with every person and try to understand their perspective while maintaining my role.

It is probably one of the hardest things I have ever had to do.

Empathize, learn the ropes of a non-specialized ICU, not let my patients die. The list goes on.

But it’s wonderful, and I have grown so much from it.

This post is long, and I’ll admit, slightly scattered, but I hope it gives you insight to a nurse’s life.

I hope you are thankful for each and every day, and never take a single moment for granted.

Life as we know it can change in an instant.

Be thankful.

Rach